Named in Antioch (Acts 11)

In the early 40s AD, a group of outsiders were given a name that would outlast empires—Christians.

Named in Antioch: When Outsiders Became “Christians” B

The usual telling stops at the nickname. The better story is how they got it—and why the mission almost stalled before it spread. This isn’t about a label; it’s about a quiet transfer of gravity from Jerusalem to Antioch. The whole story is right there: refugees spoke to Greeks, Barnabas saw grace and was glad, and the church learned to send the next team. Understand that progression, and you’ll see Acts 11 with fresh eyes.

Before diving into the full narrative, I wanted to share the heart behind this piece. This short video explains why this story of unnamed refugees matters so much—and how their "rogue" decision to speak to Greeks changed everything.

Every new movement needs a central hub. In the early 40s AD, the Jesus movement found theirs in Jerusalem.

But Jerusalem had a problem. It was a fortress. Before it was a holy city, it was a Jebusite stronghold, so confident in its defenses that its people taunted invaders, boasting that even the blind and lame could defend the walls (2 Samuel 5:6). They were wrong. That fortress mentality never left. Jerusalem was built to keep people out.

Jesus gave a clear mission: "Be my witnesses in Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria, and to the ends of the earth" (Acts 1:8). Ten years passed. The mission stalled, stuck inside the walls. The headquarters of a universal faith struggled to open its gates.

The Spark and the Getaway

Then Stephen happened.

The first Christian martyr died not by Roman hands, but by the hands of his own people. They stoned him outside the city while a young Pharisee named Saul held the coats.

This triggered a wave of persecution that scattered—fast. Most fled to familiar Jewish communities, keeping their heads down and speaking about Jesus only to other Jews. It was safe. Predictable. Controllable.

But some refugees went rogue.

Luke, the historian of this movement, drops a bombshell of a sentence: "Some of them, men from Cyprus and Cyrene, went to Antioch and began to speak to Greeks also" (Acts 11:20).

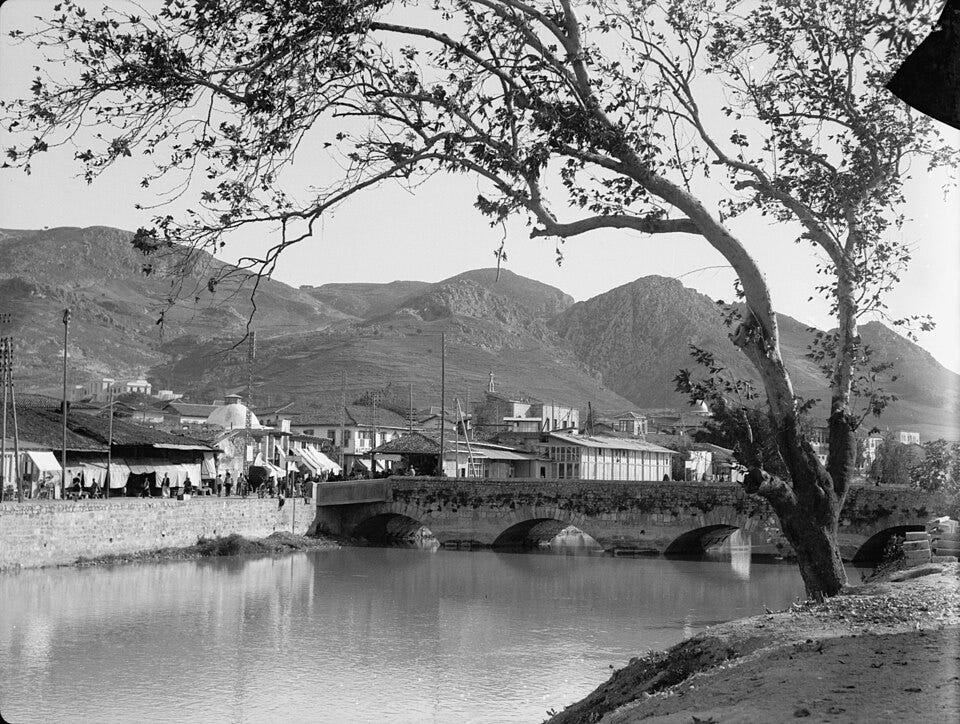

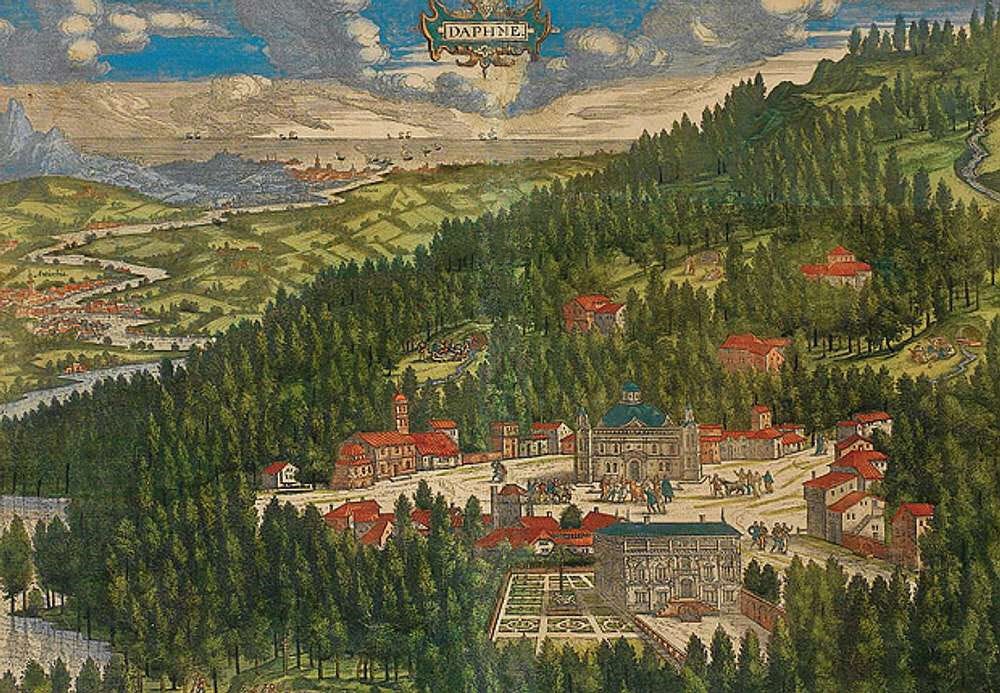

This wasn't some dusty outpost. Antioch was the third-largest city in the Roman Empire—its skyline crowded with pagan temples and its streets a chaotic mix of merchants and mischief. If Jerusalem was a fortress, Antioch was an open gate.

And into this chaos walked a few unnamed, unknown refugees who started telling Greeks about a crucified and resurrected Jewish Messiah.

The Encourager

The hand of the Lord was with them. A great number believed and turned. Greeks, Syrians, Romans—people with no bloodline to Abraham, no history with the Sabbath—followed Jesus.

News from Antioch reaches Jerusalem. It lands with a familiar vertigo. The man from Nazareth always upended expectations, but this? Uncircumcised Greeks in the Way? Wisdom demanded diligence. They needed to see it for themselves.

They needed a scout with an open heart. So they send Barnabas of Cyprus, the "Son of Encouragement." You don't send Barnabas to shut something down. You send him when you hope to find something worth celebrating.

Barnabas arrives. He stops at the threshold—voices he doesn’t recognize, bread he didn’t bless, Greeks at the table—and steps in anyway. He sees the grace of God, not a vibe, not a spreadsheet. Lives transformed. And he is glad. His face preaches before his mouth does. He exhorts them to stay faithful—and then refuses to be the hero. He goes to Tarsus, finds Saul, and makes the church bigger.

A Year in Antioch

For a whole year, Barnabas and Saul teach in Antioch. Imagine the classes. The locals watch this strange, inclusive community. They need a new word for them. They aren't Jews—too many Greeks at the table. They aren't a mystery cult—too public.

So the people of Antioch do what they do best: invent a nickname. Christianoi. Christ-followers. Those who belong to Christ.

It sticks. It is more accurate than any name the insiders chose. It identifies the movement's true center: not a city, not a law, but a Person.

The Power Shift

The center has started to move. Not away from Jerusalem’s faithfulness, but toward Antioch’s reach. From here, journeys launch and return. Here, teachers and prophets multiply. In this city they’re first called Christians—not because a committee voted, but because the Person at the center gave them a new name.

The Reversal

A prophet from Jerusalem, Agabus, arrives in Antioch. He warns of a coming famine. His words prove true. A devastating famine strikes the empire during Claudius’ reign, hitting Judea hardest.

The “suspect” church in Antioch takes up a collection. They send it to Jerusalem. No levy. No temple tax. This is the first recorded church-to-church gift.

The community that Jerusalem doubted became Jerusalem's lifeline. The refugees who fled Jerusalem ended up feeding Jerusalem. The investigated became the investors.

For centuries, money flowed to Jerusalem through obligatory Temple taxes and religious duty. Now, it flowed from grace-filled hearts in Antioch. Voluntary and joyful giving. I imagine a broad smile on Barnabas's face. The financial flip reveals the theological flip. The new faith isn't about coming to a place to pay. It is about going to all places to serve.

The pattern holds. Outsiders still become advocates. Refugees become rescuers.

Have you ever felt like you're in Antioch—off-center, invisible, suspect? Acts 11 reminds us that God builds launchpads there.

The posture that catches God's heart is still to see the grace of God and be glad.

Field Notes

Bruce W. Winter, Seek the Welfare of the City (Eerdmans, 1994)

Josephus, Antiquities 20.51–53

Suetonius, Claudius 18

Up next a midnight prison break and a church that can’t believe its own answered prayer (Acts 12).